Trump’s Cartel Crackdown Threatens to Amplify Headaches for Banks and Crypto Startups

Donald Trump's push to brand Mexican cartels as terrorist organizations could make compliance a major headache for the banking industry - and maybe even cripple the ability of crypto firms to access basic financial services. | Source: AP Photo/Evan Vucci

In a recent interview with right-wing media outlet Breitbart News , President Donald Trump said his administration is “very seriously” considering designating Mexican cartels as foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs). However, the strain this policy shift would impose on the banking industry calls into question the feasibility of an expanded counter-terrorism regime.

Donald Trump ‘Seriously’ Considering Branding Mexican Cartels as Terrorists

President Trump’s comments come on the heels of his declaration of a national emergency at the US-Mexico border last month, a move designed to secure billions more in funding for his border wall than Congress is willing to authorize. This week, the Senate revoked the border emergency declaration – a resolution the president promptly vetoed.

Designating the cartels as terrorists could, thus, serve as a maneuver to help the president gain political leverage for his controversial wall.

According to the State Department , an FTO must be a foreign organization that either engages in or has the means to engage in terrorism and “threatens the security of United States nationals or the national security of the United States.”

Additionally, the legal ramifications of the FTO designation require:

“Any U.S. financial institution that becomes aware that it has possession of or control over funds in which a designated FTO or its agent has an interest must retain possession of or control over the funds and report the funds to the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the U.S. Department of the Treasury.”

Under the “material support” provision of the law, any financial institution that fails to report terrorism-tainted funds to OFAC is subject to a civil penalty that is the greater of $50,000 per violation or twice the amount that the firm failed to disclose.

Fmr. DEA Director: Trump Should Brand Cartels as Terrorists

On the surface, designating Mexican drug-trafficking gangs as terrorists seems warranted. The atrocious, drug-related violence that has paralyzed Mexican society, and the veritable chemical warfare the cartels wage against Americans through the distribution of toxic substances like fentanyl and methamphetamine make these groups a national security threat to rival FTOs like Al-Qaeda and ISIS.

Derek Maltz, a former director of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) special operations division, told CCN.com that:

“Based on the escalating rate of murders in Mexico, the massive number of disappearances of humans, the unprecedented death and destruction of young Americans from the cartel’s poison, and the widespread corruption, I think the USA should immediately designate the ruthless cartels as terrorists.”

Homicides in Mexico rose by 33 percent in 2018 , breaking the record for the second year in a row, with investigators opening 33,341 murder probes last year, according to official Mexican government data. Furthermore, a 2018 Congressional Research Service report attributed 150,000 intentional homicides since 2006 to organized crime.

Meanwhile, in the US, a record 72,000 people died from opioid overdoses in 2017, more than all American military casualties in the Iraq and Vietnam wars combined.

US ‘Kingpin’ Strategy Creates Cartel Fragmentation

Driving the violence in Mexico is the fragmentation of criminal gangs, precipitated by a US-led “kingpin strategy” to take out top cartel leaders. The capture and prosecution of notorious Sinaloa Cartel boss Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman – and the violence that has erupted in his absence – is a prime example of this flawed approach.

Thus, as law enforcement cuts the head off of the proverbial snake, resulting power vacuums have splintered drug trafficking groups into multitudes of new gangs and set the stage for barbaric internecine fighting.

According to Latin American-focused organized crime foundation and publisher InSight Crime :

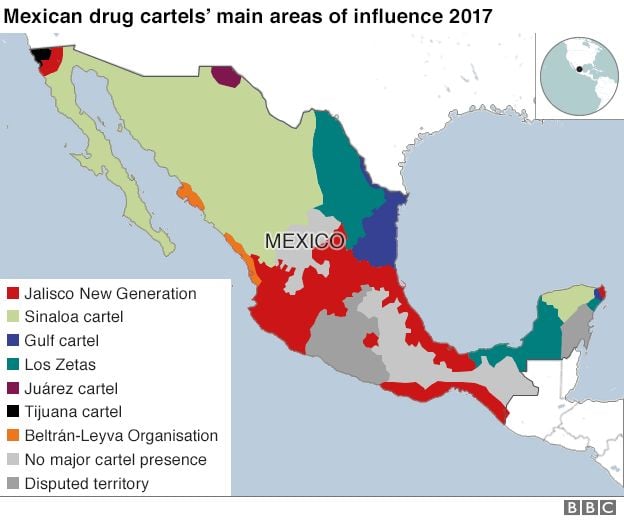

“In recent years, Mexico’s most dominant criminal organizations — The Sinaloa Cartel, Jalisco Cartel New Generation (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación – CJNG) and the Zetas — have either splintered or been threatened by smaller groups that are diversifying their criminal portfolios and using extreme violence to try and gain control of key swaths of territory.”

Today, there are no fewer than eight major criminal organizations vying for control of the Mexican drug trade and dozens, if not hundreds, of smaller gangs engaging in everything from kidnapping to extortion, oil theft, and other rackets.

‘Terrorist’ Designation Would Cause AML Costs to Surge

While Mexican cartels may satisfy the baseline criteria for FTO designation, the resultant impact could introduce crippling costs for the US banking industry, which is already spending over $25 billion per year on anti-money-laundering (AML) compliance, according to data analytics firm LexisNexis.

LexisNexis found that 67 percent of US financial services firms already “feel that AML compliance negatively impacts productivity” and that “compliance costs and operational delays are rising along with the indirect costs of increasingly complex compliance requirements.”

Although banks must already comply with the Treasury’s Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act , which overlaps the same OFAC-screening provisions reserved for terrorism-related entities, expanding counter-terrorism-financing (CTF) regimes to Mexican drug-trafficking organizations will still compound regulatory complexities and cost burdens for financial institutions.

According to Andrew Lewis, a former deputy director of the Counter Narco-Terrorism Task Force at the Department of Defense (DoD):

“Applying the FTO designation to cartels exposes banks to the risk of having the material support provision in the law being liberally construed and applied to them.”

Lewis said that when it comes to financial crimes enforcement, “the government often goes after the easiest target and the one that has money to pay the penalties which are the banks.”

“I think you would see a lot of concern in the banking industry if this moved forward, because from a risk compliance standpoint, they would have to spend so much time and money addressing potential concerns like – would the fact that individual A has an account or transferred money to individual B or business C be enough to drag that bank into court for material support to a drug cartel/terrorist if those entities were later determined to be drug dealers/terrorists and the bank didn’t do sufficient AML/KYC?”

Lewis also said that small and medium-sized banks would be especially hard hit by these expanded terrorism sanctions, which would require them to perform enhanced customer due diligence for tens of thousands or more legal entities.

According to the LexisNexis, AML compliance spend as a percentage of total assets, is already over ten times higher for smaller banks than their larger counterparts. Cost-wise, Lewis said that designating cartels as terrorists “would add significantly to the $25 billion the US banking industry is spending on AML now.”

More Headaches for Crypto

Amidst reports that Mexican cartels are increasingly using cryptocurrencies to launder narcotics proceeds, Trump’s terrorism-designation push could also compound problems for the crypto industry.

According to testimony from a December 2018 Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration, Mexican cartels are employing Chinese cryptocurrency laundering networks to conceal drug money from authorities.

Were cartels to be branded as terrorist organizations, then all of their related crypto transactions would also be subject to OFAC sanctions, according to Malcolm Wright, the chief compliance officer of blockchain firm Diginex.

“If cartels end up on OFAC then it does require proper screening to be done by crypto exchanges – something that currently has a huge disparity from nothing through to bank-grade,” said Wright.

Lewis said that increased sanctions-screening risks could make crypto firms and bitcoin exchanges even more undesirable clientele for banks due to the added OFAC burden. So far, the only instance where the Treasury has applied OFAC sanctions to the crypto-sphere was last November’s enforcement action against two Iranian ransomware operators.

Both Lewis and Wright corroborated Senate testimony and said that there is indeed evidence that cartels and criminal organizations are exploring cryptocurrency to launder money.

Lewis, who has been working crypto issues for the US government since 2013 said:

“There is cartel activity in crypto, but not to the level that I would say it is a main or relied-upon method.” He has “no doubt it will increase though.”

Trump Cartel Crackdown Unlikely to Make Much Progress – for Now

Ultimately, Lewis does not see the Trump administration designating Mexican drug-trafficking organizations as terrorists:

“…because it is a difficult process to get through the bureaucracy, and under the Drug Kingpin Act the US has many of the same abilities to sanction individuals.”

Regardless, as US foreign policy increasingly mimics the plotline for the “Sicario” sequel , any national security provision that enhances the compliance burden for US financial institutions is likely to be met with opposition by the banking industry.