Declining Profitability For New Miners Threatens Bitcoin Decentralization

The halving of the bitcoin block reward this past July has changed the profitability of new miner entries, a development that could ultimately impact bitcoin’s decentralization, according to Sveinn Valfells of Flux, Ltd. and Jon Helgi Egilsson of the Faculty of Economics at the University of Iceland.

In a paper , “Minting Money with Megawatts” for the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), the authors noted that declining profitability for new miners could further consolidate mining activity. This, in turn, could increase the likelihood of miners colluding to attack the blockchain’s bitcoin transaction history, which could threaten the cryptocurrency’s decentralized character.

Bitcoin’s architecture created a payment network independent of central banks and existing financial service providers.

Mining Mechanics

The paper goes into depth on the mechanics of bitcoin mining. Mining, a computational process, provides a key part of the bitcoin network. The bitcoin transaction ledger is distributed without central copies maintained by trusted parties. A chain of time-stamped transaction blocks comprises the bitcoin blockchain. Cryptographic hashes of the blocks secure the blockchain’s integrity. Each block references the previous block’s hash.

How Miners Are Rewarded

Miners compete to calculate valid hashes, for which they are rewarded new bitcoins, along with transaction fees. The hash is a one-way transformation of an input string, a transaction block header, into a garbled output string. The block header has several fields of data, including the prior block’s hash, a time stamp, a signature of the transactions enclosed, and a random “nonce” data field.

The block header, to be valid, must belong to the subset of outputs, each of which has a specific number of zeroes. The more zeroes, the smaller the subset, and the greater the difficulty of finding a valid hash. The hash gets computed repeatedly, varying the nonce until a discovered nonce provides a valid block header hash.

The difficulty gets adjusted every 2016 blocks to enable new blocks to appear every 10 minutes.

The block header hashes eliminate the need for a central authority to keep a copy of the blockchain. Miners compete in computing these hashes. The block reward now stands at 12.5 BTC per block.

Transaction fees use less than 1 BTC per block on average and are elective. Average annual revenues now exceed $545 million for miners.

Mining Equipment Evolves

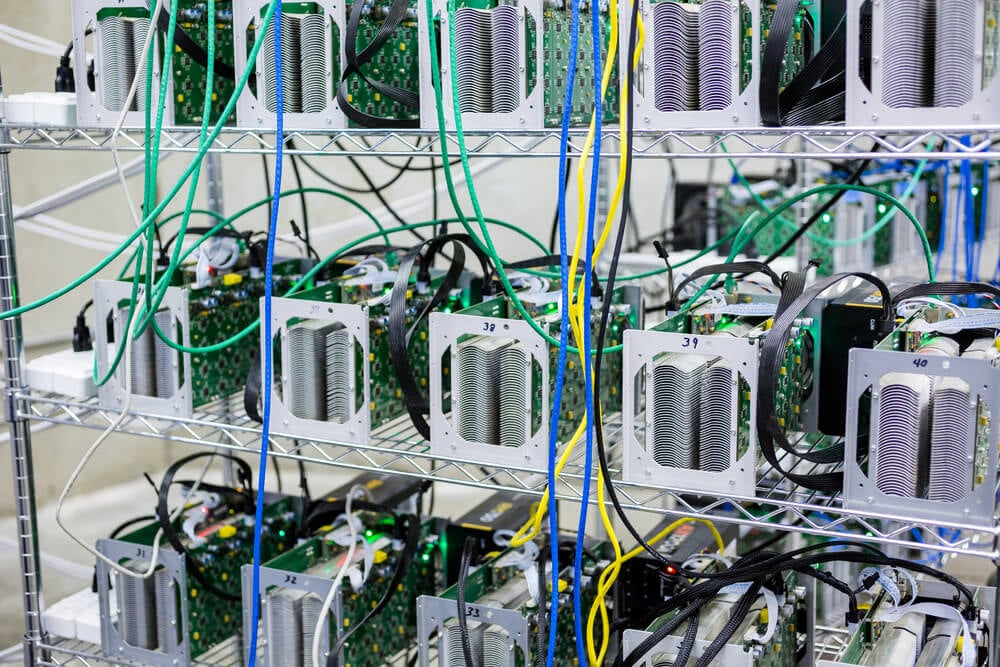

In the course of their competition, miners have progressed from graphical and central processing units in servers and desktops to application-specific processors used in custom data centers.

The biggest five mining companies and pools comprise more than three-quarters of total mining capacity, which is 1517 petahash per second. The network hash rate power use is 160 MW when mined with the latest processors. Considering older systems are still in use, the actual consumption is most likely higher.

Every miner’s share of the revenues gets diluted with added capacity. As a result, miner profits fall as the network expands.

Moreover, the new block reward falls in half every 210,000 blocks, which occurs every four years. Since transaction fees are presently around 50 times smaller than the block reward, reducing the block reward by half cuts total mining revenues if the bitcoin transaction fees and price remain unchanged.

Mining Becomes Less Profitable

The decline in mining profitability has already taken its toll on the mining community. KnCMiner declared bankruptcy in May due to the decline in the transaction block reward ahead of the July halving.

The capital costs of the latest mining facilities and systems are high, creating a barrier to entry for new miners.

Mining consolidation raises concerns about bitcoin’s integrity. The concentration of bitcoin mining increases the likelihood miners will collude to attack the blockchain. Should any entity control more than 51% of the mining capacity, it would control the blockchain’s transaction history, destroying bitcoin’s decentralized, trustless feature.

Author’s Build Economic Model

Mining’s profitability is based on economic incentives as well as the technology’s cost and performance. To analyze the market structure, the authors built an economic model to capture the main factors impacting mining profits. These include operating costs, investment costs and revenues.

New capacity can be added profitably to the mining network under the proper circumstances. The authors found that market data can determine if new entrants can add capacity profitably, the minimum cost of profitable entry, and how much capacity new entrants can add profitably. It is also possible to compute the shortest payback period.

By using recent performance and cost numbers of deployment environments and mining systems, the authors mapped the break-even zone in which new miners can add new capacity profitably. They chose a three-year amortization period that reflects that Moore’s Law doubles the processors’ peak output efficiency about every three years.

The Break-Even Zone

Considering the earlier block reward of 25 BTC at the current network hashrate, the break-even zone begins at just over $300 and fanned out with a rising price. With a current $648 price and a 1517 petahash hashrate, there was room for new entrants to more than double the hashrate. But with the block reward falling to 12.5 BTC, the lowest price at which capacity can be added profitably exceeds $600.

In addition, the minimum capacity that can be profitably added exceeds 60 petahash, while the maximum added capacity fell to 300 petahash. This is close to 20% of the existing hashrate, marking a significant barrier for new entrants and a contraction of profitable new miners.

Existing Miners Benefit

Existing miners, unlike new ones, are not restricted by the breakeven zone. They continue to operate at their capacity until their operational costs and capacity exceed revenues. They have had no reason to disable their mining equipment after the block reward fell to 12.5 BTC.

But as processors advance to Moore’s Law, power efficiency doubles about every three years. A new generation of processors with improved efficiency can grow the breakeven zone and push the lowest possible price point of new entrants to $530 from $610, partly counteracting the block reward’s halving point.

The Power Efficiency Factor

As power efficiency doubles, the lowest amount of capacity to be added profitably at the current hashrate and price falls from the current 60 petahash to 30 petahash. The maximum profitable capacity added rises to 600 petahash from 300 petahash.

The block reward’s halving has more than doubled the shortest payback period possible for new entrants to 2.8 years from 1.2 years. The post-halving payback period can fall back to 2.4 years with Moore’s Law.

New miners are close to being shut out of bitcoin mining following the recent block reward halving. They are not able to profitably add new capacity. Meanwhile, incumbents’ ability to keep mining has not been affected.

Other Factors Affect Profit

Higher transaction fees, higher bitcoin prices or a drop in existing mining capacity could improve new miners’ opportunity to enter the market. But every future block reward halving will significantly reduce the range of new miner profitability.

The distributed bitcoin ledger could become more vulnerable to attack, possibly destroying its trustless nature.

Ongoing improvement in mining processor efficiency could offset mining consolidation. And while Moore’s Law remains valid, new processors will create possibilities for new entries to the marketplace.

The greatest disruption to the existing market structure could be from the adoption of new computing technologies like quantum computers or graphine processors.