10 Blunders that Could Ground the Boeing 737 Max Forever

Boeing is taking a beating from regulators and customers alike after fatal crashes of its 787 Max aircraft over the last 6 months. | Source: Photo by CHRISTOPHE ARCHAMBAULT / AFP)

By CCN.com: While Boeing has had an otherwise commendable safety record since the 1960s, reports emerging over the past couple of days regarding the 737 Max 8 since the Ethiopian Airlines crash (and the Lion Air crash before that) have suggested that the fault could lie with the aircraft maker.

Unsurprisingly, some airlines are canceling orders of the single-aisle plane that competes with the Airbus A320neo. The most recent one is Indonesia’s national carrier, Garuda Indonesia. Garuda had ordered 50 units of the ill-fated jet model worth approximately $4.9 billion.

While announcing the cancellation it stated that ‘our passengers have lost confidence to fly with the Max 8’. The irony is that Boeing built the plane because it was what airlines were demanding.

So where did Boeing go wrong with regards to the 737 Max line of aircraft? The answers all lead to the same conclusion – it could have been prevented.

-

Inadequate training of pilots

Part of Boeing’s pitch to airlines was that the Max 8 carries the same type rating as other 737 jets. Consequently, airlines wouldn’t have to spend money on training pilots. However, the narrow-body plane has significant differences including bigger engines. The plane’s design also poses a risk of stalling in the event that pilots angle the aircraft’s nose too high.

As a solution, Boeing introduced an anti-stall feature known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS). Because the feature is supposed to function automatically and only rarely, Boeing felt there was no need to train pilots.

This has had fatal consequences. In the two Max 8 crashes, this anti-stall system has been fingered as a possible cause of the accidents.

-

Incomprehensive flying manual

While it’s one thing to skimp on training in a bid to save costs, it beats reason why Boeing provided no information on the anti-stall feature in the pilot’s manual. In the case of the Lion Air crash, the flight crew was in constant battle with the MCAS.

At one point they reached for a reference guide to figure out why the jet kept on going into dive. Unfortunately, that information was not in the flight manual. It was only after the accident that the U.S. Federal Aviation Authority directed the revision of the flying guide.

-

Excessive Automation

Though it is just one example of excessive automation, what makes the MCAS anti-stall feature even more troubling is the fact that it overrides the actions of the pilot even when it has been triggered erroneously. When triggered, this anti-stall feature nudges the plane’s nose down ready to take a dive.

In the case of the Lion Air flight, the pilot tried straightening the jet only for the MCAS to reset. What good is introducing technology that is more error-prone than the most-incompetent human?

-

Regulatory Laxity and Incompetence

According to The Seattle Times , managers at the Federal Aviation Administration pushed its safety engineers into delegating the work of carrying out safety assessment of the then new Boeing 737 MAX to the aircraft manufacturer. The basis for this? The FAA didn’t have the resources to perform its functions by itself!

Additionally, the managers also pushed for a speedy approval process. Well, if you are wondering what could possibly go wrong in such a case, read on.

-

Flawed Safety Analysis

As a result of the lack of independent safety evaluation, the results of the safety analysis were anything but competent. For instance, when the Max 8 began operating, the power of its flight control system was found to have been grossly understated by over four times.

The safety analysis also did not consider that the system did, in fact, reset itself once a pilot responded.

-

Design Flaw

In the Max 8, the activation of the MCAS is dependent on input obtained from sensors designed to read the Angle of Attack (AoA). The AoA is the angle between airflow and the plane’s wings and which determines the aircraft’s risk of staling. While the 737 Max has two Angle of Attack sensors, MCAS only relied on one. In the ill-fated Lion Air jet, the readings from both sensors differed by around 20 degrees.

Boeing has now promised a software patch that will take readings from both sensors.

-

Delays in issuing a software update

One of Boeing’s promises after the Lion Air crash was a software patch that would make its anti-stall feature safer. The aircraft had said this would be done by January. However, by the time of the Ethiopian Airlines crash, the update had not been issued. It is now expected next month.

-

Putting profits before lives

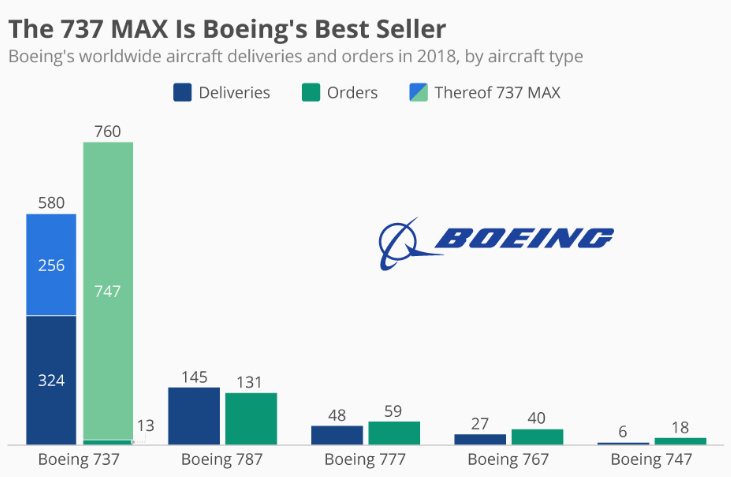

The Boeing 737 Max offers enhanced fuel efficiency (14 percent) as well as passenger capacity compared to other 737 models. Though Boeing is currently the leading aircraft manufacturer, the rushed safety analysis and certification in 2015 was as a result of Boeing’s desperation to catch up to Airbus.

At the time Airbus had just launched the A320neo. Boeing thus felt compelled to release a narrow-body passenger jet to compete with its European rival. It is safe to say that then, safety was not the Chicago, Illinois-based aircraft maker’s biggest priority.

-

Assumptions, Assumptions, Assumptions

If assumptions are the mother of all screw-ups, Boeing made too many in this case. This included assuming that pilots would only need minimal training if they were certified to fly other 737 variants. Obviously, this has turned out not to be the case.

Boeing also assumed that pilots would know exactly what to do when the anti-stall feature was activated. In the two air crashes that have since happened, the jet’s unusual behavior clearly befuddled the pilots. Who knows what else Boeing assumed.

-

Turning standard safety features into extras

With the survival rate of plane crashes being low relative to other transportation means, you would think plane makers would ensure basic safety features are standard, right? Not so with Boeing.

Per a Times report, two safety features which could have assisted pilots in detecting erroneous readings in the plane’s sensors came as extras. Now after the loss of 346 lives from the two crashes, Boeing is making one of the features free.

For Boeing, all is not lost though as it has been down this road before. In the 1960s four of its Boeing 727 jets crashed in a span of six months killing dozens.

The particular model even earned the nickname the ‘Deadly 727’ from newspapers. With the problem being instability during landing, training procedures and flight manuals were revised.

The remedial measure worked and the Boeing 727 continued production for another two decades. Its last commercial flight was in January.